In a first, researchers stabilize a promising new class of high-temperature superconductors at room pressure

The research lays the groundwork for deeper exploration of high-temperature superconducting materials, with real-world applications such as lossless power grids and advanced quantum technologies.

Researchers have made a significant step in the study of a new class of high-temperature superconductors: creating superconductors that work at room pressure. That advance lays the groundwork for deeper exploration of these materials, bringing us closer to real-world applications such as lossless power grids and advanced quantum technologies.

Superconductivity, the ability of certain materials to conduct electricity with zero resistance, typically occurs at extremely low temperatures, or in some cases, under high pressures. For decades, researchers have focused on a class of materials called cuprates, known for their ability to achieve superconductivity at relatively high temperatures. About five years ago, a team of researchers at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University discovered superconductivity in nickelates, materials chemically similar to cuprates – and last summer, another group of researchers reported superconductivity in a new class of nickel oxides at temperatures comparable to cuprates.

However, these materials required extreme pressures to stabilize their superconducting state. Such conditions could only be achieved using diamond anvil cells, specialized equipment that makes widespread study and practical applications challenging.

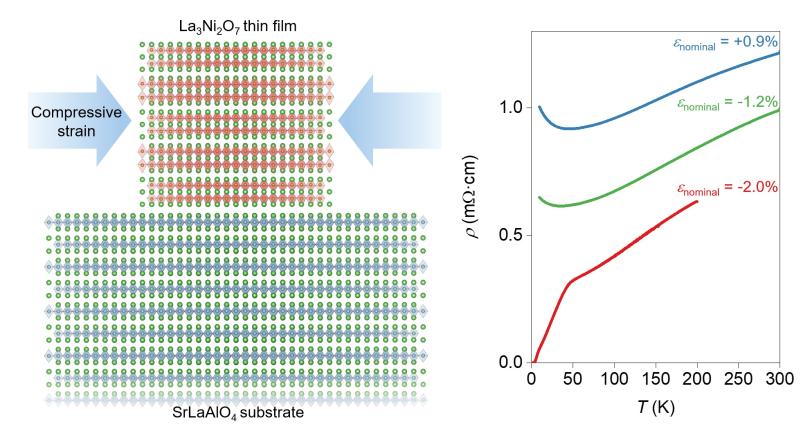

Now, the Stanford and SLAC team, led by Harold Hwang, director of the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES), have focused on thin-film growth techniques. Instead of applying external pressure, they used substrates – materials that support the thin films but also add lateral, or sideways, compression, forcing the nickelate’s atomic structure to adjust during growth. Their approach succeeded in stabilizing superconductivity in these materials at room pressure for the first time. The results were published in Nature.

The researchers observed that the material’s superconducting transition temperature ranged from -247°C to -231°C depending on the level of compressive strain. While the material enters the superconducting phase at these temperatures, defects in the nickelate and the oxygen atom ratio limit the realization of a true zero-resistance state, which was only achieved at temperatures as low as -271°C. This discovery offers a promising path for further optimization.

Studying superconductors under high pressure limits the use of advanced techniques, such as X-ray scattering, which struggles to penetrate the thick diamond cells used in high-pressure experiments. By stabilizing nickelates at room pressure, researchers can now use these tools to investigate the material’s properties in greater detail.

“The significance of this research lies in its potential to expand our understanding of high-temperature superconductors,” Hwang said. “By overcoming the limitations of high-pressure constraints, we now have the tools to conduct comprehensive studies that were previously out of reach. This work is the beginning of a much broader investigation into these novel materials.”

In addition to its experimental implications, this discovery challenges long-standing assumptions about how superconductivity works. The team demonstrated that lateral compression from substrates can stabilize the material, even though it differs from the uniform compression achieved through squeezing it evenly from all directions, similar to that produced by a diamond anvil cell. This finding provides new insights into the role of atomic spacing in achieving superconductivity.

To follow up, the researchers plan to refine the material’s crystalline quality and explore doping strategies, which involve adding small amounts of other elements to alter its electronic properties. These efforts aim to better understand the mechanisms behind superconductivity in nickelates and identify ways to enhance their performance.

Parts of this research were conducted at SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL), a DOE Office of Science user facility. This research was supported by the Office of Science.

Citation: E. Kyo Ko et al., Nature, 19 December 2024 (10.1038/s41586-024-08525-3)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.